Let me start this blog by saying that I turn 59 this year. In the midst of this pandemic I always seem right on the cusp of concern and recovery.

Concern because the impact of contracting COVID once you turn 60 increases if the statistics are any indication. On the cusp of recovery because I’ve been following Saskatchewan Health Authority tweets about the drive-thru vaccine site here in Regina, and on March 20th the age of access dropped to 59.

Since I’m still 58 until the summer, I was rechecking tweets on the hour to see if access would drop to 58. On Sunday night, March 21st, it did indeed and I was at the drive-thru for my jab. It’s now almost two weeks since my first immunization.

This is more than a matter of self-preservation. My mother, about to turn 93 and in a nursing home in Edmonton, contracted COVID last summer. Many people in her nursing home died. My siblings and I had difficult weeks expecting the worst, but she survived with remarkably few symptoms. She is now fully vaccinated with both shots. I just visited her for the first time in eight months this past week.

The tensions of the past year have become imbedded into our collective consciousness in many ways. How we relate to one another has itself become infected. Work has been, for many of us in research and academe, a never ending series of Zoom meetings and phone calls. Others on the front lines are not so fortunate and take the brunt of fear, animosity and the impatience of strangers. I try to be kind in super markets and take-aways, knowing the impact of a few good words over bad.

PTRC and Our Ongoing Social Media Dance

Mattea Columpsi, PTRC’s social media specialist, has been busy helping me with Tweets and Facebook posts concerning our news and webinars. Language, for the two of us, is an important thing and we work with our wording continuously. Last May, PTRC launched webinars about our research that included presentations from world-leading scientists. Our fifth webinar about intermediate and deep subsurface CO2 containment – jointly hosted with Carbon Management Canada – will occur on April 14th (you can register here). Taped versions of all our webinars are now streaming at PTRC’s YouTube page.

In early January we purchased a Facebook advertisement to direct people to “The Basics of Oil and Gas”, a webinar we broadcast in December. While the direction of our webinars up to that point had been technical and geared towards engineers and geoscientists, I wanted to explain to a general audience what oil exploration and production were really about. There are a lot of misconceptions in the general  population about the industry, what an oil field itself looks like (many people see it as a big underground pool and not porous rock), the methods used to get oil to market, and the research PTRC does to lessen the environmental impacts of hydrocarbon production.

population about the industry, what an oil field itself looks like (many people see it as a big underground pool and not porous rock), the methods used to get oil to market, and the research PTRC does to lessen the environmental impacts of hydrocarbon production.

We attempted to engage a wide demographic when placing the Facebook ad. I didn’t just want it going to Western Canadian oil producing areas. We targeted areas like Eastern Canada, the northern United States, and Europe – regions known for consumption of energy, not the production of it. Those who know Facebook and scrolling home feeds understand how these notices appear.

I can’t say what happened next was a surprise.

The advertisement, which took those who clicked on it to our webinar recording on YouTube, was rarely actually engaged. But comments poured in at PTRC’s Facebook page.

Most were irritated the ad even existed. Many were completely against oil and gas production. Some were vociferously in favour of it. And these two sides were drawn together to carry out a metaphysical debate about climate change, electric vehicles, the coming end of oil and gas, and other topics in our comments section.

The to-and-fro between the two sides was nasty in the usual way of on-line comments, but I was determined to edit as little as possible except where an insult was so extreme it required attention. I often interjected into the debate to remind people to be civil with each other.

I found myself defending both sides. I tried to answer any questions put directly to the PTRC – some of them difficult, dealing not simply with the financial costs associated with oil production, but rather the larger societal and environmental costs – and it became more and more clear to me that NO ONE had actually taken the time to view the webinar. No one was interested in technical information that might help shape the reality of their metaphysical arguments. Most had only read the brief description that accompanied the advertisement and immediately gotten their hackles up.

“The Basics of Oil and Gas” was just that, a technical explanation of how upstream oil and gas works, from drilling, to extraction, to monitoring, to enhanced production and, finally, to what the PTRC was doing to make production more efficient with fewer emissions.

I am aware that everything – absolutely everything – is political. I didn’t spend four years at the University of Sussex working on a D.Phil. in American Literature and Literary Theory (see Terry Eagleton for the best summary of what this is) without coming to understand the politics at work in almost everything we write. This includes the words we choose to speak, the manner in which we arrange them, the topics we include, and what we omit. But as someone in science influenced by the arts, I also insist of people that they do certain things. One of them is read. Another is observe. Another is communicate.

The Personal is Political

Perhaps the most disturbing part of the responses to our advertisement was the attacks directed at people who asked me perfectly reasonable (and yes, politically difficult) questions. People often wore their politics on their keyboards, and it was clear many were not fans of oil production. They wanted, in the immediate term, to see it end. That brought extremely angry comments from others, who clearly were earning a living in the oil patch, and who attacked questions as if they were arising out of Canadian politics and political parties.

I sent a few private Facebook messenger texts – some to Canadians in favour of oil, and some to those who were against all production and were experiencing pointed personal attacks. One such person had been with the merchant navy in England as an engineer. His observations about the impacts of oil and gas on different places he had visited around the world were not to be dismissed. And yet they were. By many. Angrily. Without context.

The observations of someone with that kind of experience are not to be dismissed so easily, and to me his points made in private to me were much more compelling than the public ones expressed by pretty much everyone at the Facebook post. Neither of us, I suppose, saw the point in expressing them in that public space where statistics were trotted out and claimed as evidence of one trend or another, leading to grandiose claims, for example, about the rise of electric cars and the demise of oil by 2030, or alternatively, individuals from resource rich regions expressing indignation at the hypocrisy of those from energy consuming regions complaining about how that energy gets produced, without either side seeming to know how interconnected both are to each other.

Oil and Gas as a Metaphor for the Pandemic Itself

So – at the risk to inciting a social media riot – here are two observations I’ve considered in the past year as I have become more immersed in virtual writing and debates about oil, climate change, and people’s visions for a future after this pandemic is under control.

1. This pandemic does not signal, at all, that hydrocarbons are about to disappear

Despite negative oil prices in March 2020, our pandemic moment does not signal anything about the end of hydrocarbons in the near or medium term. Personally, I do not believe net zero by 2050 is possible, but as a goal, sure, it’s as good a one to set as any, provided we are always ready and willing to fail.

It’s not an accident that the date of global emissions neutrality has been consistently pushed forward over and over as the truth about the way we live our lives constantly disrupts our ambitious reduction targets. I’ve seen many things trotted forth in both Canada and globally in the past twenty or more years to try to reach targets set in Kyoto and Paris. Few of them really address “cause”.

Canada’s “One Tonne Challenge” comes to mind from the Kyoto era, where the federal government, because of an unwillingness to truly regulate CO2 emissions, shifted the responsibility for reductions almost entirely onto consumers. If only we could each just reduce our footprints by one tonne – ride a bike to work, use public transit, organize car pools – Canada would magically see a 30 Mt reduction in one year. It was misguided, dishonest and didn’t work.

What governments and individuals need to acknowledge is that there is a steadfast unwillingness to acknowledge the interconnectedness of existing infrastructures and technologies to the ways people want to live their lives in the Western World, and to the rising aspirations of people in developing economies elsewhere.

Doctrinaire voices for renewables and hydrocarbons need to work together to build a realistic bridge towards a low carbon future (PTRC feels Carbon Capture and Storage is one such bridge). While oil companies, in particular, are singled out as stymieing emissions reductions, it was the President of Shell, over ten years ago, that called for a global price on carbon to make the playing field as level as possible around the world. It is fine to believe hydrocarbon use in Europe and North America will continue a downward trajectory. But can we say the same for India? Or parts of Africa and South America?

In fact, the biggest stumbling block to meaningful reductions, since the Paris Accord, has been the ongoing debates over CDM (Clean Development Mechanisms) now called Sustainable Development Mechanisms in meetings that have followed Paris. Without proper means for developing economies to receive technology transfer, it is unlikely their use of hydrocarbons will do anything but go up as their economies and middle classes expand. And who are we, in the rich Western world, to tell developing countries they can’t use their resources after what we’ve done for the past 200 years?

Electric cars are a perfect example of how Western and developing economies are diverging, and also an example of how statistics are called forth to prematurely herald the death of hydrocarbons. Recent writings during the pandemic have made much of the demise of fossil-fuel driven vehicles as one of the causes for current and future oversupply, the price collapse of oil, and the lack of a need for additional pipeline capacity. But even with ambitious targets like those recently set by the new US administration and most North American car manufacturers (GM plans to no longer make combustion engine vehicles by 2035) the math on reduced transport emissions just doesn’t add up, not with expanding automobile markets in rising economies like India, Nigeria, China and other countries.

28.2% of the United States’ emissions come from transportation, according to the EPA. This is not just automobiles and trucks, but also airplanes, trains, and other sources of transport. What eliminating combustion engines in automobiles by 2035 would mean in terms of overall reductions is not so clear cut. On March 10th of this year, the New York Times did an excellent evaluatory piece on what the rise of electric cars actually means, globally, for hydrocarbon use (Electric Cars Are Coming – How Long until They Rule the Road?).

Even if the ambitious target is reached of every new North American automobile being electric by 2035, the Times suggests that by that date, only 13% of cars on the road in the US would be electric. The average life expectancy of automobiles is 10 years and right now only 1% of new cars built in North America are electric. Even if one considers diminishing markets for combustion engines in the US and other Western economies, the article suggests that by 2050, globally, 60% of cars will still be exclusively combustion-driven. And with global populations reaching over 10 billion by that time, what are we really talking about when we talk about the end of hydrocarbons in transportation?

2. Think of hydrocarbon use not as a cause of climate change, but a symptom.

Nature reported on October 14th of last year that the pandemic had reduced emissions by 8.8% in the first six months of 2020 compared to 2019. This was largely caused by reductions in transportation as many people stayed home, air travel ground to a halt, and factories in manufacturing economies like China and Southeast Asia temporarily geared down.

“The pandemic and its metaphors” – if I can be so bold as to borrow a title from Susan Sontag’s book on AIDS – leads me to ask you all to consider this: hydrocarbons are not themselves the disease. They are the symptom. Even more boldly, I would like to suggest that hydrocarbons are not the cause of climate change. Their use and propagation are a symptom of the real causes leading us towards global catastrophe. So long as we attempt to solve climate change by attacking symptoms, the disease goes on ad infinitum, and the symptom keeps coming back.

Let me elaborate by going back to my days studying literary theory. Some of you may be aware of Michel Foucault, the French literary theorist  and philosopher. Many likely are not. And I know, having worked with geologists and engineers for all these years (including my father and two elder brothers) they are likely rolling their eyes at me. But bear with me for a paragraph or two.

and philosopher. Many likely are not. And I know, having worked with geologists and engineers for all these years (including my father and two elder brothers) they are likely rolling their eyes at me. But bear with me for a paragraph or two.

One of Foucault’s pivotal, controversial observations was to suggest that Sigmund Freud’s ideas about sexual drives were actually incorrect. Freud, stated simplistically, believed that innate biological drives were suppressed, sublimated, and redirected into other areas. Art, literature, scientific advancement, even civilization itself were the products of redirecting sexual drives into other areas of one’s life (see Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents).

Foucault took this cause-and-effect and turned it on its head. What if – and again I am stating this simplistically – sexual drives themselves were not the “cause” of civilization but, rather a symptom of it? What if other things – patriarchy, capitalism, religions, and restrictive social structures – have created “drives” to keep things moving in a particular way for the benefit of particular people?

Foucault took this cause-and-effect and turned it on its head. What if – and again I am stating this simplistically – sexual drives themselves were not the “cause” of civilization but, rather a symptom of it? What if other things – patriarchy, capitalism, religions, and restrictive social structures – have created “drives” to keep things moving in a particular way for the benefit of particular people?

In other words, what if what we thought of as a “cause” was in truth merely an “effect” or “symptom” of greater things at work.

As long as we continue to see hydrocarbons and their use as the single greatest cause of climate change, rather than a symptom of things far greater, it is unlikely we will see real and meaningful CO2 reductions.

What we’ve seen during this pandemic is impactful reductions in emissions because of reduced human activity and capitalistic consumption around the globe. But this does not mean hydrocarbons are dead or on the way out. This pandemic should tell us, in a meaningful way, that hydrocarbon use is a symptom of far greater causes. These could include authoritarian politics, subjugation of women and minorities, religious persecution, unfair distribution of wealth, exploitation of labour, and growing global populations that will peak in 2050 at over 10 billion people.

I think the utopian politics of many who believe in green consumerism, who have argued (even during this pandemic) that hydrocarbons are dead, has at its very roots a mistaken understanding of cause and effect. Hydrocarbon use should, indeed, be reduced. But to believe they won’t come back or that renewables are a magic cure ignores the disease – global structures that are the cause of climate change and the addictions those structures create.

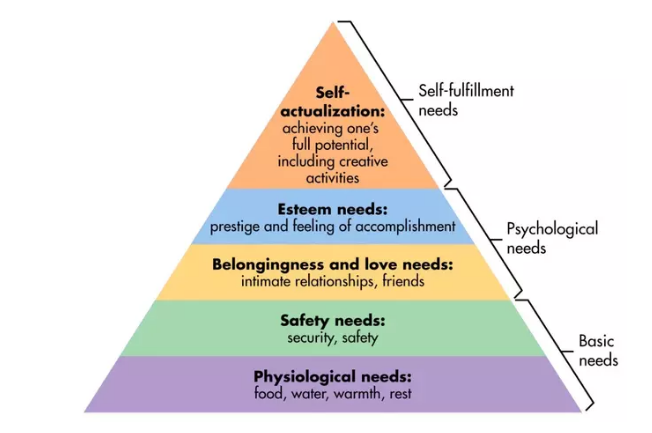

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs might be a good starting point for many (it’s still taught, after all, in many college courses) in understanding what  are the real causes at work on the “effect” of hydrocarbon use. Do we really believe a “green” economy can develop that will allow for the same level of consumerism we currently have in the West and is aspired to in the developing world? Oil is not just used for transportation, but also feeds many other “needs” that people seem unwilling to be without – computers, car dashboards, train parts, beauty products, the list goes on and on.

are the real causes at work on the “effect” of hydrocarbon use. Do we really believe a “green” economy can develop that will allow for the same level of consumerism we currently have in the West and is aspired to in the developing world? Oil is not just used for transportation, but also feeds many other “needs” that people seem unwilling to be without – computers, car dashboards, train parts, beauty products, the list goes on and on.

Perhaps we need to look at what “quality of life” actually means. Do we believe a 2050 Earth with 10 billion people, and developing economies with expanding middle class consumers, can be “green”? Recent articles I’ve read that make fantastical claims about green jobs on the horizon for us all, ignore the way current economies work, with manufacturing concentrated in certain parts of the world and the unfettered movement of capital to avoid change. I do not believe it.

PTRC has been criticized in the past for our work on carbon capture and storage (CCS) – particularly in relation to injecting anthropogenic CO2 for enhanced oil recovery, or more recently for our work on permanent storage of CO2 from SaskPower’s Boundary Dam capture plant in our Aquistore project. But the reality of hydrocarbon use is still very much with us. Reducing the carbon footprint of oil production, which is still needed for economies, or demonstrating CO2 storage safety in deep saline reservoirs so industries like steel and cement manufacturers can likewise capture and store emissions, is crucial.

To conclude, and to return to the nastiness of on-line debates I’ve experienced: can we really expect to tackle climate change without truly understanding the ways we live our lives and the structures and systems that, for good or bad, keep us interconnected? Is all this really about hydrocarbons or about so much more? Social media debates, by and large, obfuscate the truth.